A famous savage battle took place on these picturesque fields on 21 July 1403, – the Battle of Shrewsbury. The leaders of the rival armies were King Henry IV and Henry ‘Hotspur’ Percy, the son of the Earl of Northumberland.

The Percys were an influential family of Northumberland nobles, who had supported Henry Bolingbroke, as he was known before he became king, in him deposing King Richard II and taking over the crown, and later in Henry’s conflicts with the Welsh and the Scots. Henry IV’s promise of land and favours for the Percys did not materialise, and the disgruntled nobles raised an army in revolt, headed by Henry ‘Hotspur’ Percy.

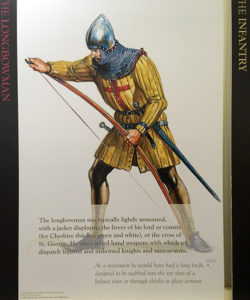

Henry Percy was the eldest son of the Earl of Northumberland. By 1403 he was already a distinguished military commander, with experience of leading troops in England and abroad. He enrolled some Cheshire arches, who were knows as longbow specialists and an expert fighting force, and headed towards the Welsh borders, to meet his uncle, Thomas Percy, Earl of Westmorland, an expert military commander.

Meanwhile Henry IV, unaware of the Percy’s revolt, was marching his army towards Scotland, hoping for the support of this powerful family in the north of England. On 12 of July he found out about the real state of affairs and turned to meet the rebel army. By 20th July both parties reached Shrewsbury and camped on the opposite sides of the River Severn a short distance from the town.

King Henry’s army of around 14,000 was bigger than the Percys’, but he was prepared to negotiate the terms. The Percys refused, and the battled commenced a couple of hours before dusk, with King Henry raising his sword.

The battle site was a field of peas at the time, which probably did not make it easy for the armies to get through!

This was the first time that the longbow was used on English soil by two English rivals against each other, and the bloodiness of the battle confirmed how effective this weapon was, with 5,000 casualties.

Among the commanders of the king’s side was his 16 year old son, Prince Henry – future King Henry V. He was hit by an arrow, which pierced his face. John Bradmore, the doctor who treated him left a detailed account of how he used specially made instruments sanitised with rose honey to remove the arrowhead stuck in Prince Henry’s facial bones. He survived and had a big scar on his face for the rest of his life.

Shakespeare put the Battle of Shrewsbury as the culmination of the play Henry IV Part 1, the conflict of Prince Henry (Shakespeare called him Prince Hal) and Hotspur taking centre stage. Shakespeare made them the same age (in reality Hotspur was about 20 years older), and in the play it is Prince Hal who kills Hotspur. In reality, it is not known who shot the arrow which finished Hotspur off, when he lifted the visor of his helmet to get a better view of the battle. His death signalled the defeat of this side and the end of the battle.

His family buried him in Whitchurch in Shropshire, but when rumours spread that he was still alive, King Henry IV ordered him to be disinterred and his salted body displayed in Shrewsbury in the marketplace pillory, later quartered and sent to various places in England, including London, with the head displayed in York, implanted on the north gate, looking towards his own lands.

Hotspur’s legacy lives even beyond Shakespeare – the name Tottenham Hotspur Football Club pays homage to this warrior, whose descendants owned land at Tottenham Marshes, near the site of their first grounds.

His uncle Thomas Percy and some other noble leaders of the rebellion were hanged, drawn and quartered in Shrewsbury on 23 July, with Thomas Percy’s head making it as far as London Bridge!

Soon after the battle a church was built near the battlefield, by order of Henry IV and funded by him, for a college of priests to pray for the souls of the dead on both sides.

The battle took places on the eve of St.Mary Magdalene’s saints day, so the church is dedicated to her.

The church became derelict by the 18th century, but was restored in the Victorian times, now boasting an amazing Victorian tiled floor. The hammerbeam roof dates from the Victorian period too. It displays the shields of knights who fought in the battle.

The church is not operation, but the building is looked after by the Churches Conservation Trust and can be visited for free by obtaining the key from the Battlefield 1403 visitor centre at the farm shop. The Battlefield 1403 complex, entitled ‘Farm Shop, Butchery ad Café’, also features a small exhibition on the battle and the weaponry used.

The walk through the fields takes several routes (not signposted or labelled), which takes one to a car part on the opposite side and back, and present a great and relaxing site on fine summer day.

Sources –

http://www.battlefieldstrust.com/resource-centre/medieval/battleview.asp?BattleFieldId=39

https://www.battlefield1403.com/

Museum display materials

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Shrewsbury

http://www.englishmonarchs.co.uk/plantagenet_45.html